猫とグルメ、初めての台湾<後編>/First time in Taiwan:Cats and fine foods<Part 2>

to Din Tai Fung, the famous xiaolongbao restaurant well known to Japanese people as well

“First Time in Taiwan (Part 2)” begins at Din Tai Fung, the xiaolongbao restaurant that is already very familiar to Japanese visitors as a legendary spot for soup dumplings.

(English text continues to the latter half of the page)

日本人にもお馴染みの小籠包の「鼎泰豐(Din-Tai-Fung)」へ

初めての台湾<後編>は、まず日本人には小籠包の名店ですっかりお馴染みの「鼎泰豐(Din-Tai-Fung)」から始めましょう。店舗は新生店(Shinshong-dien)、組織的には正式な本店ではないものの、台北中心部に位置する商売上の重要拠点。この店は常に人が押しかけており、添乗員によると最高で4時間待ちもあるらしい。ただ裏技もあり、平日の9:50までに店に来れば10:30の回の整理券をもらえる。我が家も9:20からこの列に並び、無事に整理券を入手。近くの茶葉店で買い物をして時間を潰してから、無事に10:30に入店できた。

さすがに朝からそれほど食べるわけには行かなくて、小籠包を2種類と湯葉と青菜の炒め物にエビ炒飯だけだったが、どれも絶妙なバランスをキープした味、有名になった店は“名前だけ”というところが多い中でかなりのレベルを保っていた。ちなみにビールは「賞味期限18日間」という台湾の地元ビール。

二大至宝が貸し出し中、残念過ぎた故宮博物館

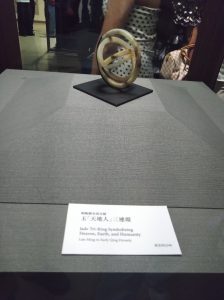

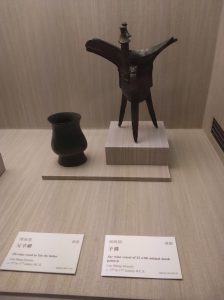

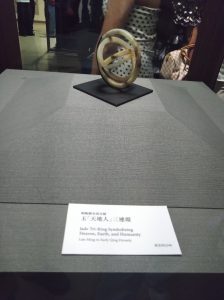

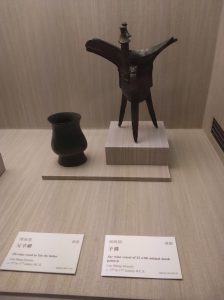

故宮博物館へはホテルからタクシーで20分、600円ほど。スケジュール通りに博物館に着いたが、その後が良くなかった。この日は朝から弱い雨が降っており、屋内での観光を優先させた団体の観光客が博物館に押し寄せ、館内は芋洗いのような混雑。しかも博物館の二大至宝である「翠玉白菜」と「肉型石」が両方(下写真参照)

ともどこかに貸し出されていて展示がない!これでは来た甲斐がない!

もちろんこれに気づいたのはすでにチケットを買って入場した後なので、帰るわけにもいかず、気落ちしながらもできるだけ多くの展示物を見て回った。

故宮博物館が所蔵する約70万点に及ぶ収蔵品は、そのほとんどが国共内戦(1948‐1949)で共産党の紅軍に対して敗色濃厚となった蒋介石率いる国民党が、紫禁城や国立施設から台湾に持ち出した国宝の数々だ。内戦で戦いながらこれだけのお宝を運び出すにはどれだけのエネルギーが必要だったのか想像もつかない。おそらくその背景にあったのは、中華民族独自の「正統意識」じゃなかっただろうか。歴代の中国大陸の王朝はどの時代でも、“天から統治を託された”シンボルとなる印璽や、国宝を所有してその『正統』の証としていた。互いに「自分こそ中華帝国の正統で、国家の未来」と主張する共産党と国民党の間で内戦が勃発し、国民党の敗色濃厚となった時に、蒋介石は敗走しながらも中華王朝の『正統』の象徴となる国宝を少しでも多く所有したかったのではないか。結果として中国大陸側を制覇した共産党政権のもとでは、その後文化大革命が起こり数多くの国宝級の文化財が破壊され、皮肉にも台湾に持ち出された国宝のために、中華古代からの貴重な資料が保存されることになった。

しかしこの日は最後までついてなかった。帰ろうとしたが正面のバス停は長蛇の列でとても乗れそうにない。博物館の受付に行ったら、ここからタクシーを呼んでやる、と言われてしばらく待っていたが、結局交通渋滞でタクシーが呼べず、博物館を出て外で探せ、ということに。それは要するに職務放棄じゃないか!実際に言われたところに出ると、タクシー待ちの人がわんさとおり、しかも列も何もない無秩序状態。結局雨の中を博物館から少し離れたところまで歩いて、たまたま見つけたバスに飛び乗った。

初めての台湾で感じたこと:高い民度と親日度合い

1.英語はほぼ通じないが、人々に悪意は見えない

観光関連施設に行っても、英語はあまり通じない。日本にいる時にはたまに台湾からの留学生と話をする機会があり、彼らはそれほど上手くなくても曲りなりに英語を話すので、現地でも日本よりも英語でいけるかな、と目論んでいたが、ほぼ日本の状況と変わりない。ただ日本語ができる人が大体いる。夜店や商店の店員は、どういうわけだか日本語の数字にはやたらと堪能。これは商売をするうえで、真っ先に抑えるべきところを押さえている気がする。また日本人にとっては漢字を観ればある程度の意味を推し量ることができるが、外国人には相当大変な旅になるだろうなと感じた。実際のところ、たまたま猴硐(ホウトン)でアメリカ人旅行者と出会って会話したが、かなり苦労しているらしい。

ただ容易に言葉が通じないところが多かったとは言え、人々に悪意のようなものは感じない。欧州などで言葉が通じない時に、現地の人間はこちらを見下げるような顔をする。若い時の自分はあの顔を見るのが嫌で一生懸命言語を勉強していた気がする。しかしここ台湾では、言葉が通じなくても粘り強くコミュニケーションをとろうと努力をしてくれ、そうしたところは聞いていた通りの“親日国”だなと感じた。それだけに台北市内の観光名所で、やたらに尊大な態度をとる日本人オヤジの団体旅行を見たのはすごく残念だった。

2.物価水準はまだら模様

少し以前であれば、台湾の物価は水準日本の半分もない、なんて巷間言われていたが、必ずしもそうでもない。外食やホテルはまだ日本よりも安いが、それでもせいぜい2割程度の差異か。過去30年間で日本がマイナス成長の中で、国自体が安くなり台湾に着実に追いつかれつつあることを肌で感じる。セブンイレブンでも多くの酒類や食料品はそれほど日本のものと大差はない。ワインなどは恐らくマーケットが小さくスケールメリットがないためか、日本の倍以上はする。

こうしたなかで公共交通はかなり安さが目立った。到着初日に悠遊カード(EasyCard)という交通系ICカードに3,000円程度をチャージしたが、台湾近郊への旅を含めて3日間目いっぱい使ったが最後まで持った。またタクシーも台北市内でどこへ行っても数百円の感覚で、移動の多い旅行者には実にありがたい。

下の写真は、日本と見まがうスーパーの食品棚と、すき家のメニュー(数字を5倍すれば日本円の水準に)

3.街は掃除が行き届き、非常にきれい

台湾は高温多湿のモンスーン気候帯で台風も多く、多くの建造物は劣化が早い。台北の街角でも多くの建物は決してピカピカとは言えないが、街の通りは掃除が行き届いて非常に清潔に保たれている。外を歩いていても清掃員をよく見かけ、夜市の喧騒の後も、翌朝にはきれいになっている。成長著しいアジアの多くの都市では、成長に専念するあまりに街のインフラが蔑ろになり、不潔な街並みや公害が問題になったりする事態も見かけるが、台北には街をきれいに保とうとする民度があるようだ。

4.水洗トイレに紙は流せない!

これまでも水洗トイレにトイレットペーパーを流せずに、片隅のごみ箱に捨てる国に行ったことがあるが、まさか台湾も同じとは!それも台北中心部のホテルの話。紙を流せないのは、下水道システムのキャパシティ不足。政府当局でもこの問題は認識されており、2017年以降に政府主導で「衛生紙丟馬桶(トイレットペーパーは便器へ流そう)」キャンペーンが始まっており、新規建築の下水道パイプを太くしたり水圧強化を行ったり、水溶性のトイレットペーパーを普及推奨したりしているが、まだまだ古いビルでは紙を流せないし、全体的にも流せないところが多数派のようだ。

5.人々は信号を守る

台北の道路は朝晩に車やバイクに溢れ、交通は結構激しい。しかし台北の人々は信号を守るし、車やバイクは歩行者がいれば車はしっかりと止まってくれる。日本のドライバーよりもはるかに歩行者に優しい。ベトナムやフィリピンのカオスのような交通事情とはまるで違う。

下の動画は、台北中心部の交差点で無限に湧き出てくるバイクの群れ

6.街に乞食がいる

東京並みに清潔に保たれた台北の街だが、東京ではほとんど見られない「乞食」の存在はショッキングだった。普通に街を歩いていても、人が集まるところには乞食がいて、前に空き缶を置いて通行人にお金を求めている。しかもそれぞれに乞食としてのスタイルを持っており、ひたすら頭を下げる者、仏教僧のようにお祈りのポーズを崩さない者、障碍を持った体を見せる者、など様々で、“職業”として乞食をやっていることを思わせる。

考えてみれば東京にも戦後長い間乞食がいたが、オリンピックや万国博覧会など、外国人が大勢来日するイベントがあるたびに、国を挙げて乞食一掃のキャンペーンを張って乞食は日本の街角から消えていった。現在でもホームレスはいても、明らかな乞食はまず見ないし、誰かが通りで乞食行為を始めたらすぐに警察が飛んできてどこかに連れて行ってしまう。いわば日本の風景から乞食が消えたのは、国の外見を気にするメンタリティだったわけで、台湾にはこうしたイベントが少なかったのか、あるいは必要以上に“外見や面子”にこだわらなかったのか、変な話だがここに文化の違いを感じてしまった。

7.戦時に備えた防空地下施設が街中に展開

台北の街中に貼られた下のパネル、実は戦時に備えた地下避難施設の場所を示すもの。これが日本との最大の違い、一見平和に見える台湾は常に中国からの脅威に備えている。逆に、平和に慣れ切っている日本は本当に今のままで安全なのかと、心に問う声が聞こえた。

to Din Tai Fung, the famous xiaolongbao restaurant well known to Japanese people as well

“First Time in Taiwan (Part 2)” begins at Din Tai Fung, the xiaolongbao restaurant that is already very familiar to Japanese visitors as a legendary spot for soup dumplings.

The branch we visited was the Xinyi (Shinsheng) store. While it is not officially the flagship from an organizational standpoint, it is a strategically important commercial location situated in the heart of Taipei. The restaurant is always packed, and according to our tour guide, the wait can be as long as four hours at peak times.

That said, there is a useful trick: if you arrive by 9:50 a.m. on a weekday, you can get a numbered ticket for the 10:30 seating. We joined the line at 9:20, managed to secure a ticket, then killed some time shopping at a nearby tea shop. Thanks to that, we were able to enter the restaurant right on schedule at 10:30.

Since it was still early in the morning, we couldn’t really eat that much. We ended up ordering just two kinds of xiaolongbao, a stir-fry of yuba and green vegetables, and shrimp fried rice. Even so, every dish maintained an exquisitely well-balanced flavor, and while many famous restaurants end up being “all name and no substance,” this one clearly kept its quality at a very high level.

The Palace Museum Without Its Two Greatest Treasures — A Huge Disappointment”

It takes about 20 minutes by taxi from the hotel to the National Palace Museum, costing roughly 600 yen. We arrived at the museum right on schedule, but things went downhill from there. A light rain had been falling since morning, so tour groups prioritized indoor sightseeing and flocked to the museum. As a result, the interior was packed wall to wall, like sardines.

To make matters worse, the museum’s two greatest treasures—the Jadeite Cabbage and the Meat-shaped Stone (see photo below)—were both out on loan and not on display. With neither of them there, it really felt like the trip had been for nothing.

Of course, we only realized this after we had already bought our tickets and entered the museum, so there was no turning back. Feeling quite disappointed, we still made our way around the galleries and tried to see as many exhibits as possible.

The National Palace Museum’s collection of roughly 700,000 artifacts consists largely of national treasures that were taken to Taiwan by the Kuomintang (KMT), led by Chiang Kai-shek, as they retreated from the Chinese mainland after suffering decisive setbacks against the Communist Red Army during the Chinese Civil War (1948–1949). It is almost impossible to imagine how much effort and energy must have been required to transport such an enormous trove of treasures while fighting a civil war.

What lay behind this, perhaps, was the distinctly Chinese concept of “legitimacy”. Throughout every era of dynastic rule on the Chinese mainland, possession of imperial seals and national treasures—symbols believed to embody the Mandate of Heaven—served as proof of rightful authority. When civil war broke out between the Communists and the Nationalists, each claiming to be the true heir to the Chinese empire and the future of the nation, Chiang Kai-shek, facing imminent defeat, may have sought to retain as many of these symbols of legitimacy as possible, even as he fled.

Ironically, after the Communists consolidated control over the mainland, the Cultural Revolution erupted, during which countless cultural relics of inestimable value were destroyed. As a result, the national treasures that had been brought to Taiwan ended up preserving invaluable materials from ancient Chinese civilization, safeguarding them for future generations.

But our bad luck continued right to the very end of the day. We tried to head back, only to find a long line at the bus stop in front of the museum—far too long to have any hope of getting on. When we went to the museum reception desk, we were told, “We’ll call a taxi for you from here,” so we waited for a while. In the end, however, they said traffic was too heavy to get a taxi and told us to leave the museum and look for one ourselves. That felt like nothing short of a dereliction of duty.

When we went to the spot they indicated, there were crowds of people waiting for taxis, with no line at all—just complete chaos. Eventually, we walked some distance away from the museum in the rain and, by sheer luck, jumped onto a bus we happened to spot.

Impressions from My First Trip to Taiwan: A High Level of Civic Mindedness and a Strong Affinity Toward Japan

-

English is rarely understood, but there is no sense of ill will among the people

Even at tourist-related facilities, English is not widely spoken. Back in Japan, I occasionally have opportunities to talk with Taiwanese exchange students, and although their English may not be fluent, they can usually manage to get by. Because of that, I had assumed that English might work better in Taiwan than in Japan—but in reality, the situation is almost the same. That said, there is usually someone who can speak Japanese. For some reason, vendors at night markets and small shops are especially fluent in Japanese numbers. From a business perspective, it feels like they have mastered exactly what needs to be learned first.

For Japanese visitors, being able to read kanji allows you to roughly infer meanings, but I couldn’t help thinking that this would be quite a challenging destination for travelers from other countries. In fact, when we happened to meet an American traveler in Houtong, he told us he was having a fairly hard time getting around.

That said, even though there were many situations where communication was not easy, I never sensed any ill will from the people. In parts of Europe, when the language doesn’t get through, locals sometimes look down on you. When I was younger, I think I studied languages so hard precisely because I hated seeing that look. In Taiwan, however, even when words don’t come easily, people patiently try to communicate, and in that respect it truly felt like the “pro-Japan country” I had often heard about. All the more because of that, it was deeply disappointing to see groups of middle-aged Japanese men on package tours behaving in an unnecessarily arrogant manner at major tourist spots around Taipei.

-

Prices Are Uneven Across the Board

Not so long ago, it was often said that prices in Taiwan were less than half of Japan’s, but that is no longer necessarily true. Dining out and hotels are still cheaper than in Japan, but the difference is probably only around 20% at most. After three decades of negative growth in Japan, you can really feel how the country itself has become cheaper, allowing Taiwan to steadily catch up. Even at 7-Eleven, many alcoholic beverages and food items are not all that different in price from those in Japan. Wine, in particular, is more than twice as expensive—probably because the market is small and lacks economies of scale.

Against this backdrop, public transportation stands out as remarkably inexpensive. On the day we arrived, we charged about 3,000 yen onto an EasyCard, Taiwan’s rechargeable transit IC card. Even after using it intensively for three full days—including trips to areas around Taipei—we still hadn’t used it up. Taxis are also very affordable: anywhere within Taipei feels like just a few hundred yen per ride, which is a real blessing for travelers who move around a lot.

The photos below show supermarket food shelves that look almost indistinguishable from those in Japan, along with a Sukiya menu. (If you multiply the numbers by five, you get roughly the equivalent prices in Japanese yen.)

-

The City Is Well Maintained and Exceptionally Clean

Taiwan lies in a hot and humid monsoon climate zone and is frequently hit by typhoons, which means that many buildings deteriorate quickly. Even on the streets of Taipei, many buildings cannot be described as shiny or brand new. That said, the streets themselves are meticulously cleaned and kept remarkably tidy. You often see sanitation workers at work, and even after the hustle and bustle of the night markets, everything is cleaned up by the following morning.

In many rapidly growing Asian cities, an excessive focus on growth has led to neglected infrastructure, resulting in dirty streetscapes and problems such as pollution. Taipei, however, seems to possess a strong sense of civic responsibility when it comes to keeping the city clean.

-

Even in Flush Toilets, You Can’t Flush the Paper!

I’ve been to other countries before where you can’t flush toilet paper even in flush toilets and instead have to throw it into a trash bin in the corner—but I never expected Taiwan to be the same. And this was in a hotel in central Taipei. The reason toilet paper can’t be flushed is the limited capacity of the sewage system. The authorities are well aware of the issue, and since 2017 the government has been promoting a campaign called “衛生紙丟馬桶” (“Flush toilet paper down the toilet”), which includes measures such as installing wider sewage pipes in new buildings, increasing water pressure, and encouraging the use of water-soluble toilet paper. Even so, many older buildings still can’t handle flushed paper, and overall, places where you can’t flush it still seem to be the majority.

-

People Obey Traffic Signals

Taipei’s roads are packed with cars and scooters during the morning and evening rush hours, and traffic can be quite intense. That said, people in Taipei obey traffic signals, and drivers—whether in cars or on scooters—properly stop when pedestrians are present. In that sense, they are far more pedestrian-friendly than drivers in Japan. The traffic situation is completely different from the kind of chaos you see in places like Vietnam or the Philippines.

The video below shows an endless stream of scooters pouring through an intersection in central Taipei.

-

There Are Beggars on the Streets

Taipei is kept almost as clean as Tokyo, but the presence of beggars—something you rarely see in Tokyo—was quite shocking. Even when simply walking around the city, you encounter beggars in places where people gather, sitting with an empty can in front of them and asking passersby for money. What stood out was that each seemed to have their own distinct “style” of begging: some repeatedly bow their heads, others maintain a prayer-like pose reminiscent of Buddhist monks, while some display their physical disabilities. It gives the impression that begging is being carried out almost as a “profession.”

Thinking back, Tokyo also had beggars for a long time after the war. However, whenever major events that attracted large numbers of foreign visitors—such as the Olympics or world expos—were held, nationwide campaigns were launched to clear them out, and beggars gradually disappeared from Japanese street corners. Even today, while there are homeless people, you almost never see overt begging. If someone were to start begging on the street, the police would quickly show up and take them away.

In a sense, the disappearance of beggars from the Japanese urban landscape reflects a mentality of being highly conscious of national appearances. Whether Taiwan simply had fewer such international showcase events, or whether it placed less emphasis on appearances and “saving face,” I can’t say—but oddly enough, this was one moment where I felt a clear cultural difference.

-

Air-Raid Shelters Prepared for Wartime Are Spread Throughout the City

The panels posted around the streets of Taipei, shown below, actually indicate the locations of underground air-raid shelters prepared for wartime. This is perhaps the greatest difference from Japan. Although Taiwan appears peaceful at first glance, it is constantly preparing for the threat from China. By contrast, Japan—having grown thoroughly accustomed to peace—made me quietly wonder whether it is truly safe to remain as it is today.