《ハンドルネームの種明かし》 「家田満」とは「Jedermann」の音訳:ナチスを産んだワイマール共和国体制と、現代日本との類似/ 《The story behind the handle name》 “Ieda Man” is a phonetic rendering of Jedermann: Parallels between the Weimar Republic, which gave rise to the Nazis, and contemporary Japan

・The screen name I’ve used for many years, Man Ieda, may sound like a typical Japanese name, but in fact, it’s a phonetic adaptation of Jedermann—a German play that symbolized the Weimar Republic (1918–1933).

The Weimar Republic was founded in 1918 after Germany’s defeat in World War I, in an effort to realize what were then the most advanced ideals of democracy. The play Jedermann came to embody the Weimar Republic itself—caught between lofty democratic ideals and the crushing burden of massive war reparations, hurtling toward eventual collapse.

(English text continue to the latter half of the page)

・自分が長年使っているハンドルネーム「家田満」、いかにも日本人の姓名に似せているが、実はワイマール共和国(1918‐1933)時代のドイツを代表する戯曲「Jedermann(ドイツ語読みではイェーダーマンに近い)」の音訳だ。第一次大戦で敗北したドイツがその反省から、当時としては世界最先端の民主主義の理想を実現しようと1918年に建国したのがワイマール共和国。戯曲「Jedermann」は高邁な民主主義の理想と、膨大な戦争賠償金の支払いという現実の狭間で破滅の方向に向かっていったワイマール共和国のアイコンと言える存在だ。

・自分がこの「Jedermann」を「家田満」にもじってみたのは、当時のワイマール体制と現代の日本にあまりに共通点が多いことを思い起こしてもらいたいためだった。高邁な民主主義の理想を掲げながら、現実の世界では膨大な経済的負担を解決する術を持たずに行き詰った末にナチスを選んでしまったワイマール共和国、そして30年間の停滞の末に歴史的な凋落が現実化しつつある現代の日本。

・第二次大戦で焦土と化した日本が奇跡の復興を遂げて世界第2位の経済大国になったのはすでに昔のこと、現代の日本は先進国から途上国レベルに凋落する近代史上で2番目の例になろうとしている。こうしたなかで戦後ほぼ一貫して政権を握ってきた自民党は政治能力も自浄能力もなくし、有象無象の新政党が政権を狙っている。その中にはSNSで支持層を固めながら、その主張はまるでオカルト団体そのもののような新興政党まである。歴史が破滅の方向に向かう最悪の政治環境は、現行政権が能力を失くしたうえに、それに取って代わるまともな勢力がない時だ。こうした時にやたらにラディカルだったり、ちょっと物珍しいことを叫ぶ連中を選んでみたりする。ワイマール共和国もまさにそうした状態でナチスを選んで、その後の歴史的破滅を決定づけた。

間違った選択をしてしまったらもう遅い。参議院選挙(7/20)を前にして、日本の有権者は歴史的な過ちを繰り返さぬために、候補者の正体を確りと見据えるべきだ。

「家田満」はワイマール共和国のアイコン「Jedermann」の音訳

自分が金融セクターをアーリーリタイアしてブログやSNSを始めたのは8年前、それまでは某大手証券の投資銀行部門でインサイドのアナリストとして働いていた。新規上場(IPO)企業や、資本戦略を抱えた上場企業に公表前から入り込み様々な分析、コンサルティングを行う業務だったので、頭の中は常にインサイダー情報で満載、どんなに細心の注意を払ったとしてもとてもSNSなどには手を出せない環境だった。そんな反動もあって会社を辞めた後はすぐに本ブログやSNSを始めているが、その際に使用したハンドルネームはいずれも「家田満」で統一した。

「家田満」というのはいかにも普通の日本人の名前のように聞こえるが、実はホフマンシュタールの戯曲「Jedermann(発音はイェーダーマンに近い)」の音訳だ。Jedermannとは英語にすればEveryman、どこにでもいる市井の人々といったイメージの言葉だ。ちなみに日本の小説家でドイツ文学に通じていた山口瞳氏は、この戯曲をもじって「江分利満氏(エブリマン氏)の優雅な生活」と、その一連のシリーズを発表している。

「Jedermann」は宗教劇の一つだ。Jedermannという名前のどこにでもいるような中年男性は信仰よりも金儲けに精を出していたが、ある日突然死神に連れ去られる。世俗の欲望にまみれた彼は、神の前での審判で救われることはあるのか、というキリスト教社会で最も普遍的な問いかけを描いている。初演は1912年だが、1920年にザルツブルク(オーストリア)でフェスティバルが開始され、以後はワイマール共和国時代を象徴するアイコンとなり、1938年にナチスがオーストラリアを併合してからもナチスの庇護を受けて毎年野外劇として上演が続いている。

自分がこのワイマール共和国時代のアイコンであるJedermannをもじったハンドルネームを選んだのは、やがてはナチスを産みだす当時のドイツの情勢と、現代の日本の政治経済の状況があまりに似ているのではないか、と恐れているからだ。

世界最先端の民主主義の実現を目指したワイマール共和国はなぜ行き詰ったのか

ワイマール共和国は第一次世界大戦終了後の混乱の中で1918年に建国された。当時のドイツは第一次大戦の敗北と、ベルサイユ条約で課せられた天文学的な賠償金で先に希望が見いだせない状況、しかしこうした絶望の中で人々は過去の失敗から脱却し、当時の世界では考えられない水準の民主主義国家の建国に向かった。これがワイマール共和国の誕生だ。その憲法では、男女の同一参政権、議会制民主主義と法治国家、憲法に基本的人権を明記、連邦制・政教分離・社会権の明記など、20世紀初頭とは考えられないほど近代的で高邁な民主主義の理想を掲げて建国された。

しかし共和国はその後順調に歴史を刻んだわけではない。何といっても敗戦によって負った犠牲が大きすぎた。民族としての敗北感もさることながら、ベルサイユ条約によってドイツに課せられた賠償金は1,320億金マルク、これは当時の国家予算の10年分以上に相当し、まともに支払いきれないことは目に見えていた。さらにそうした経済的負担に、1929年の「暗黒の木曜日」に代表される世界大恐慌が覆いかぶさる格好となり、国内は歴史的なハイパーインフレとなり経済は壊滅的な状況に陥った。こうした苦境の中で政権は安定することなく、比例代表制による小党乱立により連立政権は相次いで崩壊、そのうちに反民主的勢力が政治の舞台に入り込むことで政情は混乱し、いわゆる「民主主義の自己破壊性」が現実化している。民主主義の高邁な理想を掲げながら現実の苦境を切り開くことはできず、国全体に行き詰まり感が充満していく。

現代の日本にもこうした情況で当てはまるものはないだろうか。もちろん当時のドイツが課せられた賠償金負担は天文学的なもので、現代の日本と比べるべきではないが、30年間も成長から取り残され、名目GDPでは世界2位からすでに4位(まもなく5位)に滑り落ち、グローバルな競争力では世界トップから38位に凋落し今後の成長も望めず、特に将来への絶望感が強く、国民は恒常的に減少していく所得を消費に回さず貯めようとするばかり。そもそも社会保険料の負担増加と、コストプッシュインフレの高騰で可処分所得は減少する一方だ。政府の間では企業の定年を75歳に設定し、年金受給を80歳からにするなんてとんでもない極論まで議論されている。そうなると日本人は50年以上働いた末に人生最後の2、3年間だけ年金を受給するというまさに近代社会としての終末を思わせるディストピアの様相を呈する。短期的なイベントとしては、90年代以降継続していた「低成長・低賃金・低インフレ」というバランスがこの2、3年で急速に崩れ、低成長と低賃金はそのままに、外部要因によるコストプッシュインフレでインフレ率、生活コストだけが大きく昂進している。特に日本人の主食であるコメの価格は異常気象と政府の無策も相まって、この1年で倍以上に値上がりしている。まさにフランス革命前夜のような状況に陥り、むしろ日本人が暴動を起こさないのが不思議なくらいだ。こうした国民の一人一人に国力の衰退が押し付けられているなかで、どす黒い閉塞感が日本社会の内部で醸成されつつある。

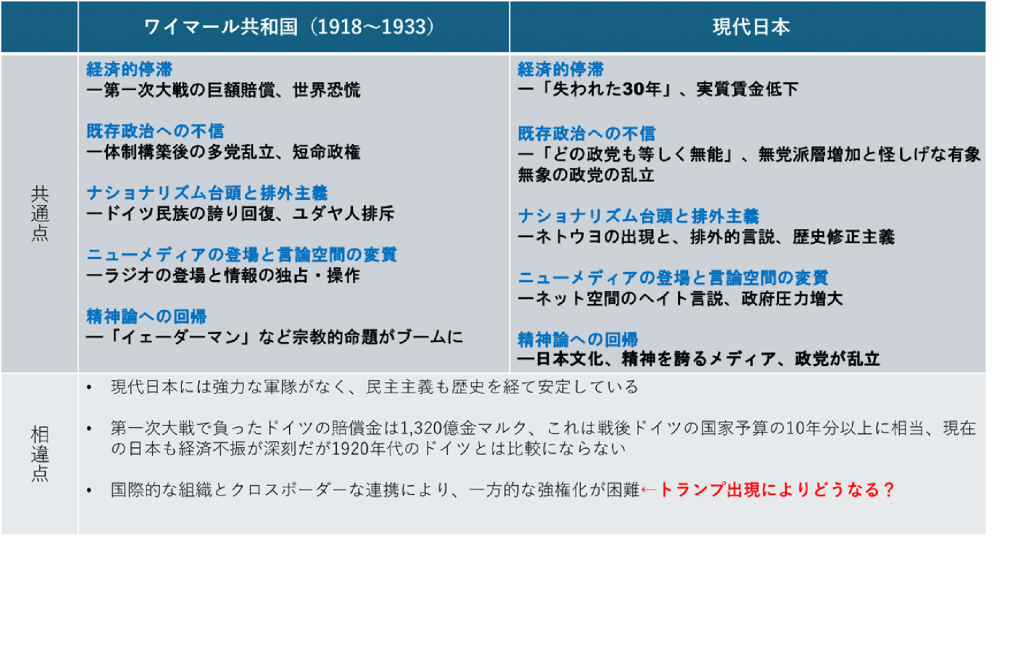

下の図で当時のワイマール共和国と現代の日本との比較を試みた。

政治経済的な類似点のほか注目すべきなのは、社会に広がる「精神論への回帰」だ。これは現実が行き詰まった時に現れる“社会の現実逃避”と呼べるもの。「イェーダーマン」のような宗教道徳劇が人気を得たのも、先行きの見えない現実から目を背けて何か高尚なものだけ見て安らぎを得たい、という心理が強烈に影響していなかっただろうか。「イェーダーマン」という演目はその後、アーリア民族の道徳的に優れた文化の代表としてナチスの庇護を受けて盛んに上映され続けた。1929年から始まる世界恐慌の暴風を受けて国内景気は壊滅的な状況となり、1930年の選挙ではそれまで12議席だった国家社会主義ドイツ労働者党(ナチス)の議席が107議席と大躍進し第二党のポジションを得て、混迷を極める政府の中で決定的な権力を掌握するのに短い時間しか要しなかった。1930年の躍進からわずか3年後の1933年にヒトラーは首相の指名を受け、ワイマール共和国はここで崩壊した。悪名高いゲシュタポの前身組織もこの年に作られている。ファシズムと民族浄化の狂気に彩られた破滅の始まりだ。

現代の日本でも「文化」が重要なキーワードだ。TV番組を見ると「外国人旅行者は誰しも日本文化に夢中」と言いたげな番組が毎日流れる。しかしこれ以前の日本が誇っていたのは、優秀な工業製品や高い経済成長力だったはずだ。やたらに過去の遺産である文化や精神面を云々し始めたら、国としての成長はすでに現在進行形ではなくなったと見た方がいい。さらに「文化や伝統」といったことだけだったらいいが、これが「大和民族精神の復活、世界一優秀な民族と国家」などといった“独りよがりの妄想”に走り出したら、社会全体が一気に間違った方向に向かいかねない。現代の日本に必要なのは、根拠のない思い込みを強めることではなく、かつての成長と輝きを取り戻すための地味で具体的な努力のはずだ。

間近に迫った参議院選挙、日本の将来はここで問われる

今週末の7/20(日)は参議院選挙だ。国政選挙となるわけだが、すでに連立与党である自民・公明党は経済環境の悪化と度重なる石破首相の失策で大きく支持を落としており惨敗となるのは必至だ。そうなると上院である参議院での過半数を保つこともできなくなるため、第三の党と連立与党を組むことになる。ここを目指して、現在有象無象の新興政党がSNSを駆使しながら選挙戦を展開している。その中でも“躍進”という表現で既存メディアからも注目されているのが、神谷宗幣氏率いる『参政党』だ。党名だけを聞くと「若者も政治に参加すべき」という主張を思わせるが、その実態は「日本人ファースト」をキャッチフレーズにした《オカルトと陰謀論・民族主義と排外、ヘイト》に凝り固まったカルト集団だ。

これまでの主だった言動を見るだけでも、

<明治維新の裏には国際ユダヤ資本がいた>

<コロナワクチンを射つと死亡率が上がる>

<年齢の高い女は子供を産めない、女子中高生は3人子供を産んでから進学すればいい>

<小麦粉は戦後にアメリカによって持ち込まれた、戦前に日本に小麦粉の料理はなかった>

<メロンパンを食べて翌日に死んだ人が大勢いる>

<ガンは戦後に生まれた病気>

<天皇は側室をもつべき>

<日本は核以上に強力な武装をすべき、国防のためにはドローン部隊を組織し、全国のゲーマーに防衛させる>

もはや枚挙に暇がない、こうしたまったく幼稚で根拠のない主張に加え、自己啓発セミナーの主催、正体不明の「波動水」、「波動米」などスピリチュアル商品の販売など、彼らは政党というよりもカルト集団と呼ぶべき存在だろう。さらに党首の神谷氏は、きわめて他人への支配欲が強い人間で、一切の反論を許さないタイプの人間らしい。昨年末には最も身近にいたはずの秘書が自殺に追い込まれている。

しかしこのフェークと誤情報だらけの集団が参院選を前に着実に力を増している。ここにワイマール共和国の時代と同じ類の「大衆によるパラドックス」を感じてしまう。彼らが標榜する『日本人ファースト』というキャッチフレーズは、トランプ大統領の「America First」が元祖になっている。小池百合子都知事はこれをそのままコピーして「都民ファーストの会」を立ち上げたが、これは単なるパクリで何の実績も挙げなかった。これに対して参政党の『日本人ファースト』には歴史的な危険性を感じざるを得ない。国内政治が機能不全となり国民が自信を失くした時に、最も大衆の心に刺さる思想は「外部勢力の排斥」だ。ナチスがユダヤ人を大衆の敵として設定したように、参政党やその他の保守勢力は日本人の人口減少とともに増加しつつある外国人労働者や留学生を排除しようとしている。またこれはトランプを選んだアメリカにも共通することだと思うが、陰謀論には多くの大衆が「おれの人生がうまく行かないのは陰謀のせいだったのか」と安心させてくれる効果がある。参政党の主張には、衆愚を惑わす仕掛けがそこら中に散りばめられている。

しかし彼らの「日本人ファースト」が、いつまでも日本人を守ってくれるとは到底思えない。彼らが政界で力を増すにつれて、『日本人』の定義はどんどん狭まる。最初は「働いていない高齢者、子供を持たない夫婦、障碍を持った国民、LGBTQ」などは日本人に含まれないとなり、最終的には「参政党(自分)を支持しない」のは日本人ではない、となる。ナチスがどのように独裁体制を強めていったのかをもう一度学んでみよう。

80年代末にオウム真理教という新興宗教団体がいた。彼らは荒唐無稽な主張を掲げて当時の国政選挙に乗り出し惨敗した。当時の日本社会がこの安直な週末論やオカルトのデパートのような宗教団体に対して抱いたイメージは「荒唐無稽なことばかりやってるけど、人畜無害な連中」といったものだった。そのわずか5年後の1995年に、彼らは猛毒化学兵器のサリンやVXガスなどを自前で精製し、13人の死者と6,000人以上の負傷者(このうち4,000人余りが今でも後遺症に苦しんでいる)を出す「地下鉄サリン事件」を起こした。

ワイマール共和国がナチスを選んだ当初も、国民の間ではヒットラーのことを「オーストリアのチビの伍長」と揶揄するものも多かった。しかしそれからわずか数年でナチスは独裁と虐殺の体制を整え、かつてナチスに異を唱えた勢力を処刑していった。

参政党の支持者の中には彼らの荒唐無稽で間違いだらけの演説を面白がって彼らに票を投じる向きも多いように感じる。しかし選んでしまった後に何が起こるのかを想像した方がいい。選挙に行くことは“1億分の1の権利”を行使することだ。日本が歴史的な転換点を迎えようとしているこの時に、間違った選択だけはしてはならない。

悪魔は道化師の顔をして現れる

・The screen name I’ve used for many years, Man Ieda, may sound like a typical Japanese name, but in fact, it’s a phonetic adaptation of Jedermann—a German play that symbolized the Weimar Republic (1918–1933).

The Weimar Republic was founded in 1918 after Germany’s defeat in World War I, in an effort to realize what were then the most advanced ideals of democracy. The play Jedermann came to embody the Weimar Republic itself—caught between lofty democratic ideals and the crushing burden of massive war reparations, hurtling toward eventual collapse.

・I chose to render Jedermann as “Ieda Man” in order to highlight the many unsettling similarities between the Weimar regime of that era and contemporary Japan. The Weimar Republic, despite its aspirations for high-minded democracy, was unable to resolve its harsh economic realities and ultimately turned to the Nazis. Likewise, after thirty years of stagnation, Japan now seems poised to enter a historical decline.

・The miraculous recovery that lifted Japan from the ashes of World War II to become the world’s second-largest economy is already a thing of the past. Today’s Japan is on track to become the second case in modern history of a developed nation sliding into the ranks of the developing world. In this environment, the Liberal Democratic Party, which has held power almost continuously since the end of the war, has lost both its political competence and its capacity for self-correction. Meanwhile, a swarm of new and disorganized parties is vying for power.

・Among them are emerging movements that, while building their base through social media, promote ideas that are barely distinguishable from those of occult cults. The worst political environment arises when a ruling government loses its ability to govern, and there is no credible alternative. That’s when people start turning to radical or eccentric voices simply because they seem new or different. This is exactly what happened in the Weimar Republic, which ultimately chose the Nazis and set itself on a path to historical catastrophe.

Once a wrong choice is made, it’s already too late.

With the upcoming Upper House election on July 20, Japanese voters must clearly recognize who the candidates truly are—so as not to repeat the tragic mistakes of history.

The name Man Ieda is actually a phonetic rendering of Jedermann, the cultural icon of the Weimar Republic

I began writing blogs and engaging on social media eight years ago, shortly after taking early retirement from the financial sector.

Until then, I had worked as an in-house analyst in the investment banking division of a major securities firm.

My job involved analyzing and consulting with companies preparing for IPOs or managing complex capital strategies—often from the inside, well before any information became public.

Because my head was constantly filled with insider information, I had to be extremely cautious. Engaging in social media under such conditions was simply unthinkable.

Perhaps as a kind of reaction to that environment, I immediately launched my blog and social accounts after leaving the firm, and since then, I’ve used the same handle across all platforms: Man Ieda.

At first glance, Man Ieda sounds like a perfectly ordinary Japanese name.

But in fact, it’s a phonetic rendering of Jedermann, the German-language play by Hugo von Hofmannsthal (pronounced something like “Yé-der-man”).

Jedermann translates into English as “Everyman”—an archetype representing the common, everyday person.

Incidentally, the Japanese novelist Hitoshi Yamaguchi, who was well-versed in German literature, drew inspiration from this play when he created his series “The Elegant Life of Mr. Eburi Man” (a clever play on the word “Everyman”). Jedermann is a religious drama.

The titular character is an ordinary middle-aged man more devoted to money-making than to faith.

One day, however, he is suddenly summoned by Death. Drenched in worldly desires, he now faces divine judgment—can he be saved?

It’s a dramatization of one of the most universal themes in Christian societies. Although the play premiered in 1912, it became a signature production of the Salzburg Festival beginning in 1920. During the Weimar Republic era, Jedermann came to symbolize that tumultuous period in German history. Even after Austria was annexed by the Nazis in 1938, the play continued to be performed annually as an open-air production, with the regime’s full endorsement. The reason I chose Jedermann—this emblem of the Weimar Republic—as the basis for my online handle is because I fear that the political and economic climate of that time in Germany bears a disturbing resemblance to present-day Japan.

Back then, as now, a democratic society with high ideals was drifting toward disaster.

Why the Weimar Republic, Which Aspired to the World’s Most Advanced Democracy, Ultimately Stalled

The Weimar Republic was established in 1918 amidst the chaos following the end of World War I. At that time, Germany faced a seemingly hopeless situation—defeated in the war and burdened with astronomical reparations imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. Yet in the midst of this despair, the people sought to break free from past failures and move toward the creation of a democratic nation of a kind unimaginable in the world at that time. This was the birth of the Weimar Republic.

Its constitution set forth ideals of democracy that were remarkably modern and ambitious for the early 20th century: equal suffrage for men and women, parliamentary democracy, the rule of law, explicit constitutional guarantees of basic human rights, federalism, separation of church and state, and the recognition of social rights.

However, the republic did not proceed smoothly through history. Above all, the sacrifices borne from defeat in the war were simply too great. Beyond the national sense of humiliation, the reparations imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles amounted to 132 billion gold marks—more than ten times the national budget at the time—making it obvious that proper repayment was unfeasible. On top of this economic burden came the global Great Depression, epitomized by the “Black Thursday”, stock market crash of 1929. The result was a historic hyperinflation that plunged the German economy into a catastrophic state.

Amid this hardship, political stability proved elusive. The proportional representation system led to a proliferation of small parties, causing coalition governments to repeatedly collapse. In time, anti-democratic forces began to enter the political arena, bringing turmoil and triggering what is often referred to as the “self-destructive nature of democracy.” Though the republic stood for noble ideals of democracy, it was unable to overcome the harsh realities it faced, and a sense of stagnation spread throughout the entire nation.

Is There Nothing in Contemporary Japan That Resembles This Situation?

Of course, the astronomical burden of reparations imposed on Germany at the time cannot be directly compared to the situation in present-day Japan. However, Japan has been left behind in terms of growth for over 30 years. Its nominal GDP has already slipped from second to fourth place in the world (soon to be fifth), and in terms of global competitiveness, it has fallen from the very top to 38th place. With little hope for future growth, there is a pervasive sense of despair about what lies ahead. People are increasingly reluctant to spend their earnings and instead choose to save, as household incomes continue to decline.

To begin with, the rise in social insurance premiums and the soaring cost-push inflation are steadily eroding disposable income. Within the government, there are even extreme proposals being discussed, such as setting the retirement age at 75 and beginning pension payments only from age 80. If such measures were to be implemented, the result would be a dystopian image of a modern society where people work for over 50 years and receive a pension only in the final two or three years of their lives.

In the short term, the delicate balance of “low growth, low wages, and low inflation” that had persisted since the 1990s has collapsed rapidly over the past two or three years. While low growth and low wages remain unchanged, external factors have triggered a sharp surge in cost-push inflation, leading to soaring inflation rates and living costs. Especially notable is the price of rice, the staple food of the Japanese people, which has more than doubled in the past year due to a combination of abnormal weather and government inaction.

Japan now seems to be in a situation eerily similar to the eve of the French Revolution—it is almost puzzling that no riots have broken out. With each citizen being forced to bear the brunt of national decline, a deep and murky sense of stagnation is beginning to permeate Japanese society.

Below is a diagram attempting a comparison between the Weimar Republic and present-day Japan:

-1024x657.png)

Beyond Political and Economic Similarities: The Resurgence of “Spiritualism” in Society

In addition to political and economic parallels, what deserves particular attention is the societal shift toward a “return to spiritualism.” This can be seen as a form of social escapism that emerges when a society finds itself at an impasse. The popularity of religious-moral plays like Jedermann may have stemmed from a powerful psychological desire to avert one’s gaze from an uncertain and bleak reality, seeking solace in something lofty and transcendent. The play Jedermann later came to be promoted under the Nazi regime as a symbol of the morally superior culture of the Aryan race and continued to be widely performed under its patronage.

The global economic crisis that began in 1929 devastated the German economy. In the 1930 elections, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nazi Party), which had held only 12 seats, made a dramatic leap to 107 seats, becoming the second-largest party. It took only a short time after that for them to seize decisive power within an increasingly paralyzed government. Just three years after their breakthrough in 1930, Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor in 1933, marking the collapse of the Weimar Republic. That same year, the notorious Gestapo’s predecessor organization was also established—signaling the beginning of a descent into the madness of fascism and ethnic cleansing.

In contemporary Japan as well, “culture” has become a key buzzword. Television programs are filled with messaging that implies “every foreign tourist is fascinated by Japanese culture.” Yet, what Japan once took pride in was its outstanding industrial products and impressive economic growth. When a nation begins to emphasize only its past cultural and spiritual heritage, it may be a sign that it is no longer progressing in the present.

Worse still, if the focus on “culture and tradition” morphs into a self-indulgent delusion—such as talk of “reviving the Yamato spirit” or proclaiming that Japan is the most superior nation and people in the world—then society risks veering rapidly in a dangerously misguided direction. What modern Japan needs is not to indulge in baseless fantasies, but to engage in modest, concrete efforts to recapture the growth and brilliance it once possessed.

The Upcoming House of Councillors Election: Japan’s Future Hangs in the Balance

This Sunday, July 20, marks the House of Councillors election. As a national election, it comes at a critical time: the ruling coalition of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and Komeito has already seen a sharp decline in support due to worsening economic conditions and repeated blunders by Prime Minister Ishiba. A crushing defeat now seems inevitable. If they lose their majority in the upper house, they will be forced to form a coalition with a third party.

With this in mind, a wide array of emerging parties is currently mounting aggressive campaigns using social media. Among them, the one attracting significant media attention—often described as “surging”—is the Sanseitō (means The Party of Political Participation, their official English party name is Sanseito Party of Do It Yourself), led by Mr. Sohei Kamiya. Judging by its name, one might assume the party promotes youth involvement in politics, but in reality, it is a cult-like group rooted in slogans such as “Japan First,” and steeped in occultism, conspiracy theories, nationalism, exclusionism, and hate speech.

A brief look at the party’s key statements reveals the following:

“The Meiji Restoration was orchestrated by international Jewish capital.”

“The COVID vaccine increases mortality rates.”

“Older women cannot bear children; junior high and high school girls should give birth to three children before going on to higher education.”

“Wheat flour was introduced to Japan by the U.S. after World War II; there were no wheat-based dishes in prewar Japan.”

“Many people have died the day after eating melon bread.”

“Cancer is a disease that only appeared after the war.”

“The Emperor should have concubines.”

“Japan should be armed with weapons even more powerful than nuclear arms; for national defense, drone units should be formed and gamers across the country should be mobilized to defend the nation.”

The list goes on and on. In addition to such absurd and unfounded claims, they also host self-help seminars and sell suspicious spiritual goods like “wave-infused water” and “wave-infused rice.” This group is far closer to a cult than to a political party.

What’s more disturbing is the character of their leader, Mr. Kamiya, who appears to be highly controlling and intolerant of any dissent. In fact, at the end of last year, his own secretary—someone who worked closely beside him—was reportedly driven to suicide.

Despite being a cesspool of misinformation and fakery, this group is steadily gaining strength as the election approaches. Here, one cannot help but sense a “paradox of the masses” reminiscent of the Weimar Republic. Their slogan, “Japan First,” is a clear derivative of former President Donald Trump’s “America First.” Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike copied it verbatim in her creation of “Tomin First no Kai” (Tokyo residents First), which produced no meaningful achievements. By contrast, Sanseitō’s “Japan First” carries a far more dangerous historical weight.

When national politics fall into dysfunction and the public loses confidence, the ideology that resonates most with the masses is “the rejection of outsiders.” Just as the Nazis positioned the Jews as public enemies, Sanseitō and other far-right forces are beginning to target foreign workers and international students—whose numbers are rising as Japan’s native population shrinks.

This, too, mirrors the rise of Trump in the United States. Conspiracy theories provide many ordinary people with a sense of relief: “So my life hasn’t gone well because of some conspiracy.” Sanseitō is riddled with psychological traps that play directly into this sentiment, preying on mass confusion.

But their vision of “Japan First” will not protect the Japanese people forever. As their political power grows, the definition of “Japanese” will only become narrower and more exclusive. First, they may exclude “the elderly who don’t work,” “couples without children,” “people with disabilities,” and “LGBTQ individuals” from the category of real Japanese. Eventually, they may go so far as to declare that “those who do not support Sanseitō are not Japanese.” We must revisit how the Nazis steadily expanded their dictatorship and purged dissenters.

At the end of the 1980s, there was a new religious group called Aum Shinrikyo. They ran in national elections, spouting bizarre claims, and were overwhelmingly rejected. At the time, the public largely viewed them as a harmless oddity—“ridiculous, but not dangerous.” Yet just five years later, in 1995, they carried out the Tokyo subway sarin gas attack, having produced deadly chemical weapons like sarin and VX gas themselves. Thirteen people were killed, over 6,000 were injured, and more than 4,000 still suffer long-term effects today.

When the Nazis first gained political traction in the Weimar Republic, many Germans mocked Hitler as “that short Austrian corporal.” But just a few years later, the Nazi regime had consolidated its power through dictatorship and mass killings, systematically eliminating anyone who once opposed them.

Among Sanseitō supporters, there seem to be many who find amusement in their wild and nonsensical speeches and are tempted to vote for them for entertainment. But it’s worth imagining what might happen after they are elected. Voting is the exercise of your one-in-a-hundred-million right. As Japan stands at a historic turning point, we must not make the wrong choice.